The Monarch Life Cycle

Monarchs (Danaus plexippus plexippus) leave overwintering sites in February and March and typically reach the northern limit of their North American range in early to mid-June. Adult females lay eggs singly on milkweed species (primarily Asclepias spp., but occasionally on other closely related species as well, including Gomphocarpus spp. and Calotropis spp.), which the caterpillars rely upon for energy and protective toxins called cardenolides. Milkweeds are critical for successful development of the caterpillar into an adult butterfly. Once an egg is laid, the full cycle to adulthood may last 20 to 35 days (sometimes longer) depending on temperature. The caterpillars develop through five instars before forming a chrysalis and pupating into an adult butterfly. During the spring and summer, adult monarchs spends their 2–5 week lifespan mating and nectaring on flowers, with females searching for milkweed upon which to lay their eggs. Multiple generations are produced during this time, with the final fall generation migrating to overwintering sites and living for 6–9 months.

Egg

Appearance: Eggs are 1.2 mm high and 0.9 mm wide, cream or yellow in color, with longitudinal ridges running from the tip to the base.

Length of stage: Eggs hatch about 4 days after they are laid, with development slower under cooler conditions.

Life history: Monarch females usually lay eggs singly on a milkweed plant, often on the bottom of a leaf near the top of the plant; however, eggs can also be deposited on milkweed flower buds, stems, and the top sides of leaves. The dark head of the developing caterpillar can be seen near the top of the egg just prior to emergence.

Larva

Larvae molt as they grow and the stages between larval molts are called instars. Each new instar grows and expands until the outer skin splits, the head capsule falls off, and the new larva is able to crawl out of its skin. Monarchs go through 5 larval instars, which are distinguished by the monarch’s head size and presence and length of filaments on their thorax and abdomen. Development time from egg through 5th instar stage takes about 9-16 days, depending on temperature. Size is not a good determinant of instar. In the larval stage, monarchs are eating machines growing up to 2,000 times their original mass.

1st Instar

Appearance: Newly hatched larvae are 2-6 mm long, with pale green or grayish-white, shiny, and almost translucent bodies and a distinct black head. The body does not get its characteristic white, yellow and black stripes until after ingesting milkweed. The body is covered with sparse setae (hairs). Older first instar larvae have dark stripes on a greenish background.

Life history: After hatching, the larva eats its eggshell (chorion). It then eats clusters of fine hairs on the bottom of the milkweed leaf before starting in on the leaf itself. It feeds in a circular motion, often leaving a characteristic, arc-shaped hole in the leaf. First (and 2nd) instar larvae often respond to disturbance by dropping off the leaf on a silk thread, and hanging suspended in the air. Time in this larval stage is usually 1-3 days, depending on temperature.

2nd instar

Appearance: Second instar larvae have a clear pattern of black, yellow and white bands, and the body is no longer transparent and shiny. Look for a yellow triangle on the head and 2 sets of yellow bands around this central triangle to distinguish the 2nd instar. Setae on the body are more abundant, and look shorter and more stubble-like than those on 1st instar larvae.

Life history: Time in this larval stage is usually 1-3 days.

3rd instar

Appearance: The black and yellow bands on the abdomen of a 3rd instar larva are darker and more distinct than those of the 2nd instar, but the bands on the thorax are still indistinct. The triangular patches behind the head are gone, and have become thin lines that extend below the spiracle (respiratory opening). The yellow triangle on the head is larger, and the yellow stripes are more visible. The first set of thoracic legs is smaller than the other 2, and is closer to the head.

Life history: Time in this larval stage is usually 1-3 days. Third instar larvae usually feed using a distinct cutting motion on leaf edges. Unlike 1st and 2nd instar larvae, 3rd (and later) instars respond to disturbance by dropping off the leaf and curling into a tight ball.

4th instar

Appearance: Fourth instar larvae have a distinct banding pattern on the thorax which is not present in 3rd instars. The first pair of legs is even closer to the head, and there are white spots on the prolegs that were less conspicuous in the 3rd instar.

Life history: Time in this larval stage is usually 1-3 days, depending on temperature.

5th instar

Appearance: The body pattern and colors of 5th instar larvae are even more vivid than that of the 4th instar, and the black bands looks wider and velvety. The front legs look much smaller than the other two pairs, and are even closer to the head. There are distinct white dots on the prolegs, and the body looks plump, especially just prior to pupating.

Life history: Fifth instar larvae move much farther and faster than other instars, and can be found far from milkweed plants as they seek a site for pupating. Time in this larval stage is usually 3-5 days, depending on temperature.

Pupa

Just before pupation, a monarch larva will spin a silk pad from spinnerets on the bottom of its head and clasp onto it with hooks from its hind prolegs. It can then hang upside down. After splitting its exoskeleton and wriggling around to remove its larval skin, a cremaster appears. This stem-like appendage is hooked into the silk pad and allows the pupa to safely hang until it emerges as an adult (see black “stem” at the top of the pupa in the photo to the right).

Life history: While the process of complete metamorphosis looks like 4 very distinct stages, continuous changes actually occur within the larva. The wings and other adult organs develop from tiny clusters of cells already present in the larva, and by the time the larva pupates, the major changes to the adult form have already begun. During the pupal (chrysalis) stage this transformation is completed.

Just before the monarchs emerge, their black, orange, and white wing patterns are visible through the pupa covering. This is not because the pupa becomes transparent; it is because the pigmentation on the scales only develops at the very end of the pupa stage. The pupal stage lasts about 8-15 days.

Adult

Adult monarchs typically live 2-5 weeks during their breeding season. However, the migrating generation doesn’t reach maturity until overwintering is complete (about 6-9 months).

Life history: Adult monarchs emerge (eclose) after about 2 weeks as a chrysalid. At eclosure, the abdomen contains most body fluids and wings are shrunken. The adult hangs upside-down and pumps fluids into wings until they expand and stiffen, then flies and feeds on nectar plants (often milkweed).

Adults reach sexual maturity in 3-8 days. When mating, the male and female stay coupled from one afternoon until early the next morning, sometimes up to 16 hours. Females begin laying eggs immediately after mating and both sexes can mate several times during their lives.

Male and female monarchs can be distinguished easily. Males have a black spot on a vein on each hind wing that is not present on the female. The ends of the abdomens are also shaped differently in males and females, and females often look darker than males and have wider veins on their wings.

Monarchs sequester a cardenolide toxin acquired as larvae from their milkweed host plants. This toxin makes them unpalatable to some predators as larvae and adults. They advertise this toxin with their brightly colored wings and larval stripes.

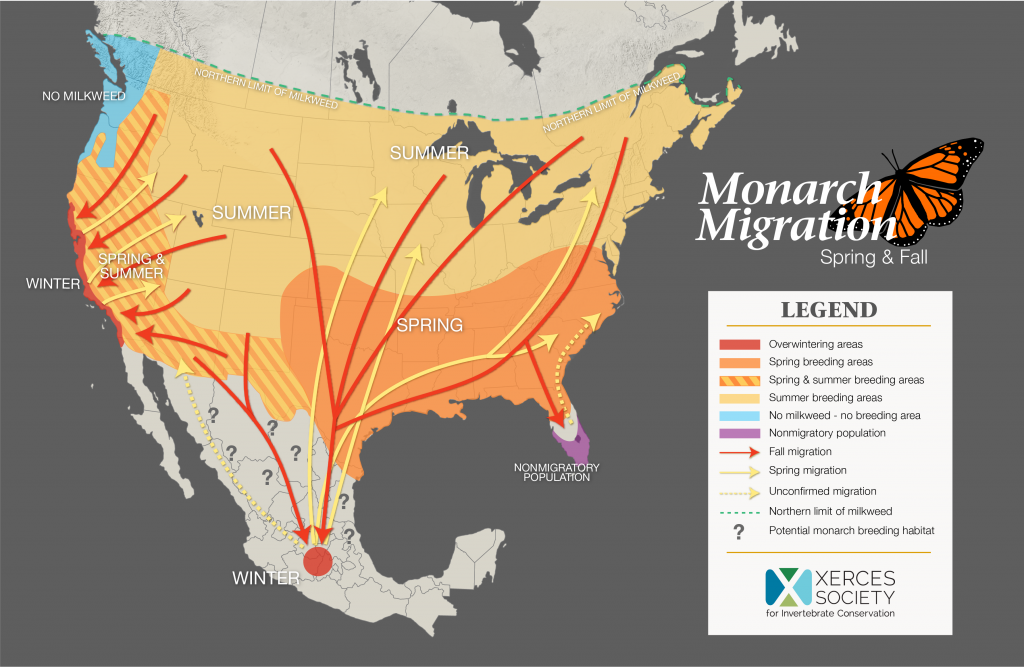

Migration and Overwintering Behavior

The monarchs’ migration from the eastern U.S. to the mountains of central Mexico is a widely known phenomenon. In the 1990s, nearly 700 million monarchs made the epic flight each fall from the northern plains of the U.S. and Canada to sites in the oyamel fir forests north of Mexico City. And while fewer people are aware of a smaller migration of monarchs from breeding areas in the West to the California coast and, to some extent, the mountains of central Mexico, this population too once numbered over one million butterflies. Today, only a fraction of these populations remain. Researchers and community scientists have documented declines of over 80% at the Mexican overwintering sites and 95% along the California coast.

Western monarchs aggregate in clusters at forested groves scattered along 620 miles (1,000 km) of the Pacific coast from California’s Mendocino County to Baja California, Mexico. Small aggregations inland from the coast have also been reported in Inyo and Kern Counties in California and in several sites in Arizona. The distribution of monarchs among overwintering sites changes over the season and annually, based on regional and individual site conditions.

The majority of overwintering sites along the Pacific Coast are located within 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of the Pacific Ocean or San Francisco Bay. Monarchs seek out very specific microclimate conditions, including dappled sunlight, high humidity, access to fresh water, and an absence of freezing temperatures or high winds. Fall and winter-blooming flowers provide nectar which may be needed to maintain lipid levels necessary for spring migration. The tree species most commonly used for roosting are the nonnative blue gum eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus), Monterey pine (Pinus radiata) and Monterey cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa). Clusters can also be found on nonnative red gum eucalyptus (Eucalyptus camadulensis), and the native western sycamore (Platanus racemosa), coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), and others.

Monarchs begin arriving at these overwintering sites in September and the first half of October, forming fall aggregations. By mid-November, they have formed more stable aggregations that persist through January or into February. The butterflies cluster in dense groups on the branches, leaves, and sometimes tree trunks. The adults usually remain in reproductive diapause throughout the winter, and activity is limited to occasional sunning, hydrating, and nectaring. In late winter or early spring, the surviving monarchs breed at the overwintering site before dispersing. Climate change and other factors may contribute to divergence from these overwintering behaviors or the timing thereof.

For many years, it was assumed that monarchs west of the Rocky Mountains overwinter on the Pacific coast while monarchs east of the Rockies migrate to central Mexico. Tagging efforts have shown that wild monarchs tagged in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Arizona, and Nevada migrate to the California coast. Additionally, an isotopic study at five California overwintering sites suggest the natal origin of a large proportion of the overwintering monarchs come from either coastal Southern California or Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

Learn more about Western monarch tagging efforts and tag recoveries here.

However, the Continental Divide has proven to be more permeable than originally thought. The eastern vs. western population migration model was built on very limited evidence. Monarchs tagged in Idaho and Washington have been recovered in Utah as well as California, suggesting a second, southerly migration route. More recently, monarchs tagged in Arizona have been recovered in central and western Mexico, as well as coastal California. Furthermore, genetic studies have concluded that the western and eastern populations are not genetically distinct. These findings support hypotheses that some portion of western monarchs travel to Mexico for the winter, some portion of eastern monarchs travel to the western United States after overwintering in central Mexico, and/or there is interbreeding of eastern and western monarchs during the breeding season, likely in the Intermountain West. The relative rate of exchange between the eastern and western populations is currently unknown and isotopic studies have generally omitted isoscapes on either side of the Continental Divide. Hence, while population trends at California overwintering sites provide an index of the western population, they do not represent the entire western population.

Read more about monarch population trends here.